Course Authors

Eli A. Friedman, M.D.

Dr. Friedman has received grant/research support from Alteon within the past three years.

Estimated course time: 1 hour(s).

Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center designates this enduring material activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Albert Einstein College of Medicine-Montefiore Medical Center and InterMDnet. Albert Einstein College of Medicine – Montefiore Medical Center is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Upon completion of this Cyberounds®, you should be able to:

Describe complications of peritoneal dialysis caused by inadequate phosphate removal

Discuss why synthetic vitamin D and calcium carbonate are given to dialysis patients

Describe the effects of excess parathyroid hormone in renal failure.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old white female with insulin dependent type II diabetes was placed on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) because of deteriorating renal function from diabetic nephropathy. Several weeks after the initiation of dialysis, painful necrotic lesions began to appear on the thighs and legs in what seemed to be "kissing distribution." Skin biopsies performed at that time indicated tissue ischemia due to thrombosis. A work-up for a hypercoaguable state was inconclusive except for a finding of a reduction in functional protein S activity. There was no history of Coumadin® use.

The patient's initial laboratory data included:

| Creatinine: 11.4 | Calcium: 8.6 |

| BUN: 81 | Phosphorus: 8.9 |

| HCT: 29.8 | PTH: 353 |

| Alk Phos: 153 | Hgb A/C 6.3 |

| CPK: 48 | Protein C Activity: 87 |

| Protein S Activity: 49 | Protein S antigen: 156 |

| ESR>130 |

With the development of more lesions and their spread, primarily in the upper thigh and buttock region, the patient experienced incapacitating pain and a downward clinical course ensued.

Requests for repeat biopsies were denied. Several X-rays and CAT scans taken, during this time, of the thigh and hip were unremarkable except for the presence of extensive vascular calcification consistent with the patient's underlying diabetes.

Figure 1.

The lesions pictured here developed about one month after dialysis was begun. They were extremely painful and were initially described as "being on fire" by the patient. As time progressed, these wounds became infected and contributed to a septic state that was responsible for her demise.

Figure 2.

The results of the patient's terminal lab data were:

| Creatinine: 4.1 | Calcium: 8.1 |

| BUN: 55 | Phosphorus: 5.4 |

| HCT: 30.6 | PTH: 117 |

| Alk Phos: 468 | ESR>130 |

| SGOT: 2 | SGPT: 18 |

| TProt: 5.2 | Alb: 1.3 |

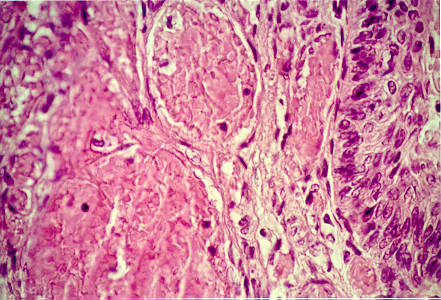

A biopsy taken at autopsy of the thigh lesions revealed thrombosis as the primary pathology.

Figure 3.

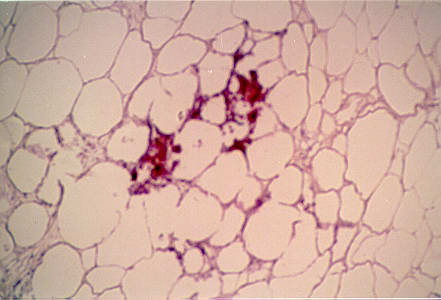

Secondarily, calcification was present in the adipose layer as pictured here.

Figure 4.

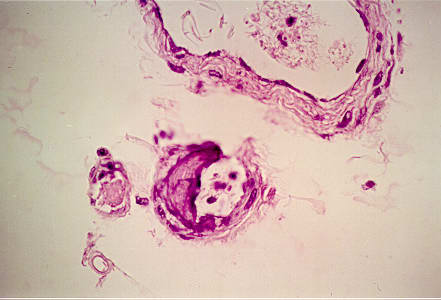

Lastly, mural calcification was seen in some small (50 microns) arteries.

Figure 5.

Q. What's your diagnosis?

Discussion

Almost immediately after initiating maintenance hemodialysis in the early 1960s, the deleterious effects of inadequate phosphate removal became a major problem in patient management. Canner and Decker described a new variation in "pseudogout," manifested as painful swelling of the fingers, wrists, elbows, and knees in association with both hyperuricemia and a calcium-phosphorous concentration that exceeded its solubility product.(1) Microprecipitation of calcium-phosphate complexes were then recognized as toxic manifestations of uremia presenting as "red eyes" (2) and skin necrosis.

Clarification of the role of inorganic pyrophosphate(3) in the crystal induced arthropathy of uremia(4) permitted distinction, in 1973, between the pseudogout of osteoarthropathy and the pseudogout related to indolent secondary hyperparathyroidism in renal failure. Both disorders reflect precipitation of calcium pyrophosphate from supersaturated joint and interstitial fluid.(5)

By 1976, a syndrome of tissue necrosis and vascular calcification - termed calciphylaxis by Gipstein et al. - was attributed to hyperphosphatemia and secondary hyperparathyroidism.(6) Lesions of calciphylaxis seen in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis and renal transplant recipients are characterized by medial calcinosis of arteries, painful ischemic ulcers of fingers, legs, and thighs, and skin necrosis. Necrotizing livedo reticularis is a rare but life-threatening complication of chronic renal failure that may be noted in calciphylaxis or in parathormone toxicity without other vasculopathy.(7)

An especially virulent form of systemic calciphylaxis has been reported after successful kidney transplantation, when previously silent secondary hyperparathyroidism is unmasked as fulminant tertiary hyperparathyroidism (no hypercalcemia).(8) Total parathyroidectomy, without autotransplantation of parathyroid tissue,(9) and subtotal parathyroidectomy(10) have been successfully applied to cure the syndrome of fulminant calciphylaxis, in single case reports.

Hyperphosphatemia reciprocally depresses plasma ionic calcium levels, a reaction that in turn stimulates the parathyroid glands to secrete excess parathormone, thereby increasing bone dissolution by osteoclasts. Renal osteodystrophy is the term applied to the common syndrome in renal insufficiency resulting from decreased renal synthesis of active vitamin D plus parathormone generated bone demineralization, pathologic fractures, and calcium pyrophosphate deposition in soft tissues (secondary hyperparathyroidism).

Treatment of hyperphosphatemic uremic patients on or off hemodialysis was first based on addition of aluminum hydroxide phosphate binders to the dialysis regimen. Concurrently, very large doses of fish liver derived vitamin D were administered to maximize intestinal absorption of calcium. Although aluminum hydroxide lowered the plasma phosphate concentration, the gel caused nausea, was constipating, and after long-term use was found to be the cause of dialysis dementia - a new iatrogenic variety of aluminum intoxication. Few patients were able to tolerate the gastrointestinal disturbance that was constant during large dose fish liver oil therapy.(11)

Coping with the dual risks of calcium pyrophosphate joint and tissue deposition and renal osteodystrophy, clinicians advocated subtotal parathyroidectomy for many dialysis patients through the mid-1980s. Once the pathophysiologic basis for these doctor-manufactured signs and symptoms of partially treated renal failure became clear, an alternative strategy for bone protection was devised that persists to this day. Once the strikingly greater potency of 1 alpha hydroxylated synthetic vitamin D compared with fish liver oil was appreciated,(12) a three component regimen(13) consisting of:

- limiting dietary phosphorus,

- complexing phosphorous in the gut (calcium carbonate replacing aluminum hydroxide as the phosphate binder),

- daily doses of synthetic vitamin D titrated against the ionized plasma calcium level that should approximate normal (9-10.5 mg/dl).

Problem patients persist as illustrated by the present patient. Note the high phosphorous of 8.9 mg/dl. While hindsight always evinces wisdom, parathyroidectomy might have been life saving. It would have been extremely interesting to learn the size of the parathyroid glands. My guess is that they were huge.

In summary, calciphylaxis is a sporadic, life threatening complication of deranged calcium-phosphate metabolism in renal failure. Probably an expression of excess parathormone secretion resulting from hyperphosphatemia induced hypocalcemia, calciphylaxis has been successfully managed by urgent subtotal or total parathyroidectomy.

Readers are invited to report their own experience with this rare complication. Especially welcome will be accounts of nonsurgical management.